Flight

Janet Biggs, 1999

Four-channel SD video installation with sound

Running time: multiple loops of 2 to 4 minutes

Whether in the story of Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek mythology, or Lady Godiva's legendary ride, the horse is a symbol of ecstatic flight and apotheosis; its sexual potency contained therein. Not surprisingly, in the 15th-century A.D., Pope Calixtus III—referring to the pagan worship of horses still prevalent at the time—decreed that no more religious ceremonies should be held in “the caves with the horse-pictures,” and punished the image-makers accordingly.

In Flight, artist Janet Biggs re-envisages the heterodoxical horse and all its ancient allusions to explore issues of modernity, gender, and desire. As a psychoanalytic trope for female sexual sublimation, the majestic creature has become a constant in her work—a leitmotif that takes up the social and psychic implications of sexual identity. In previous video installations, for example, the artist depicted young girls “playing horsey” with adults, riding mechanical horses, and performing in competitions.

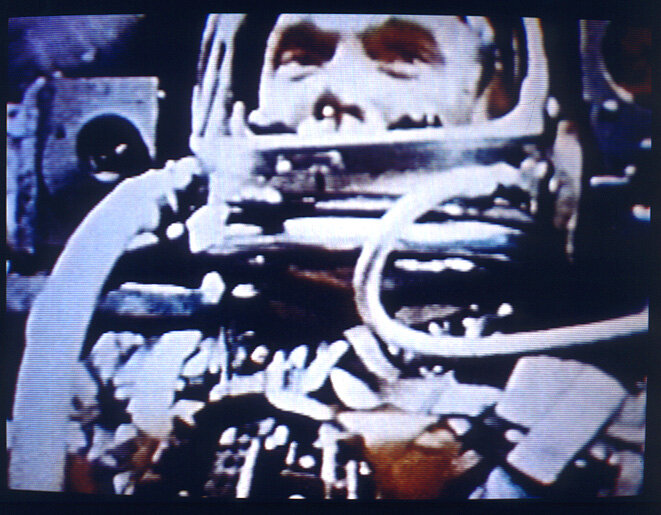

Biggs created Flight as a site-specific work for Wesleyan University's Zilkha Gallery—an L-shaped, cavernous space with limestone walls and 28-feet-high ceilings. Engaging the architecture's spatial grandeur and, alternately, what she saw as its bunker-like quality, her installation combines an official NASA photograph of John Glenn with a series of multi-channel video projections—three that feature synchronized swimmers and one, a sleeping horse.

Depicted in full space-suit regalia, and in his capsule, John Glenn’s portrait alludes to romantic notions of progress, conjuring a time when America’s competition with the Soviets and the influence of the Cold War culminated in a desire to colonize space. Glenn’s picture is the first image the viewer encounters, and as such sets the tone of the installation. Through its placement, Biggs evinces the machismo of a culture whose nostalgia for heroes comes full circle with the aging astronaut’s recent return to space.

Glenn’s image, auratic and foreboding, is made more so by Flight’s audio component. Intercut with the repetitious sounds of a rocket blast-off, snippets of Glenn's space-to-ground communication, and the ecclesiastic techno-beats of the musician Moby, its intermingling of triumph and panic create a din of technological hubris: one moment we hear Glenn say he is okay, and the next we hear attempts to regain contact with him when he is lost on the satellite.

The picture of Glenn and the projected sleeping horse (presented in gargantuan, drive-in scale) conceptually frame a wall of images that depict three separate swimmers. Both are, in their respective defiance of gravity and dream-like state, portraits of bodily transcendence. Positioned at either end, they create a surreal reciprocity with the swimmers, who inverted, also appear to be flying.

While Biggs’ synchronized swimmers hardly resemble those that Busby Berkeley featured in his musicals of the early 1930s, it was these filmic spectacles that in part inspired their imagery. Its true her subjects—members of a senior team—do not convey the same tawdry excitement, nor titillate the viewer in an extravaganza of costume and choreography, yet they nonetheless arouse our looking. Sexual, and for that matter, sexualized, they arrest our vision in a state of disbelief. Can these strong bodied, self-possessed athletes really be elder women? Against the virile portrait of Glenn, and our knowledge of his recent return to space, our ambivalence becomes addled by the otherworldly nature of the swimmers’ movements. Seen upside down, their inverted bodies perform endless “schooling figures,” every muscle engaged as they ready themselves for competition. And all the while they appear weightless.

It is through making her swimmers’ strenuous activity seem effortless and transcendent that Biggs reveals the masquerade of femininity; all the effort that goes into making things appear “natural” or easy. Moreover, the topsy-turvy view she constructs embodies not just an implosion of passive/active, subject/object binaries, but the paradoxical position she holds in relation to her subjects. As female and voyeur, author and participant, artist and rider, her “gaze” constitutes something contradictory yet real. Destabilizing conventional notions of gender as well as critiques of the “male gaze,” her view fetishizes femininity and concurrently resists it.

The horse in Flight similarly speaks of a gendered performance, one that is “masculine,” though equally contrived. Like the horse in Biggs’ Water Training, 1997, whose eyes bulge as he struggles to stay above water, he too subverts our sense of the familiar, and refuses our expectations. Indeed, we encounter not an icon of dignity and vigor, but a vulnerable creature—supine and nearly still.

Sustained looking eventually relieves the viewer's discomfort that the equine is ill or dead. Periodically his hind legs twitch and jerk. Our relief, however, is mitigated by his equivocal movements. Is it joy or fear that drives his imagined flight? Like the flying swimmers, and the audio's intermittent pandemonium, Biggs complicates what we see (or hear) with what we know. In the end, it is these new equations of beauty and strength, age and desire, gender and masquerade that transform the viewer.

Jane Harris is a New York-based critic who contributes to various publications including Art in America, BOOKFORUM, and art/text.